Clarifying Rules Engines with Clara Rules

Feb 28, 2017

This blog is the transcribed overview of the talk I gave at the Clojure/conj 2016 conference. Watch the talk for more in depth details.

I have been working with rules engines extensively for the last four years. A rules engine can be a powerful tool at your disposal for managing complex, potentially volatile, “business” logic. I have experience using rules engines to efficiently evaluate thousands of rules against hundreds of thousands of data points. The algorithmic techniques used by these engines have been around for over 30 years now and have been used across many domains.

Throughout the rest of this discussion, I will use Clara rules to demonstrate my points. Clara rules is an open-source rules engine written in Clojure by Ryan Brush. Clara rules has been used in production workloads for several years. To compare, JBoss Drools is a popular, mainstream rules engine available on the JVM. Clara has performed competitively with Drools against production-scale workloads.

What are rules engines?

When discussing rules engines, I’m referring to forward-chaining inference engines that evaluate rules against a dataset. I’m specifically discussing rules engines based on the Rete algorithm. This is an algorithm that was introduced in the 1980’s. Most modern-day rules engines are based on some variation of the Rete algorithm.

The first thing to understand when discussing rules engines is what a rule is. A rule is really nothing more than a simple if-then conditional construct:

(defrule a-rule

<condition0>

<condition1>

<condition2>

=>

<action>)

There is no “else” for a rule. The rule is either satisfied or not satisfied. The “if-side” conditions, i.e. before the => in the syntax, are typically referred to as the Left-Hand Side (LHS). The action on the “then-side”, i.e. after the =>, is referred to as the Right-Hand Side (RHS).

When a rule has all of its conditions in the LHS satisfied, the rule is considered activated, which means it is eligible to be fired by the rules engine. Firing a rule means to execute the action expression on the RHS.

Rules are evaluated against a dataset. The memory that holds this dataset is called the working memory. The individual data points within working memory are called facts.

The RHS action of a rule can update the state of working memory. A RHS action can insert new facts, retract existing facts, or update existing facts in working memory. In this way, rules can interact with other rules to express more complex conditional logic.

The job of the rules engine is to evaluate a set of rules against some initial state of working memory.

The basic rules engine algorithm is:

- Find rules with all LHS conditions satisfied, i.e. activated.

- Fire one of these activated rules.

- If rules are still activated, repeat from step 1.

Clara rules syntax

Let’s do a quick overview of Clara rules syntax for writing rules.

(defrule rule-a

[FactType1 (constraint-fn x :some-value) (= ?y-binding y)]

=>

(insert! (->ThingA ?y-binding)))

defrule is a Clojure macro. It just defines a rule with the name given by the symbol coming after defrule. Here the rule name is rule-a. The => symbol separates the LHS (if-part) from the RHS (then-part) of the rule. A rule has zero or more conditions on the LHS. Each condition is surrounded by square brackets. In this rule, there is a single condition. The condition starts with a fact type of FactType1. In order for a fact in working memory to match this condition, it must have the type FactType1.

After the fact type, the condition can have zero or more additional constraints. A fact must match the fact type and satisfy all of the constraints of a condition in order to satisfy the condition. constraint-fn is an arbitrary function that is used as a predicate. x is a field name of a fact matching the fact type FactType1. Clara syntax allows you to directly refer to fields of the facts being tested against.

The constraint (= ?y-binding y) is special. It is not testing for something to be satisfied about a fact, but rather it is creating a binding of the symbol ?y-binding to the value of the y field of a fact matching this condition. Symbols starting with ? in rules are called variable bindings. They can be thought of as local bindings in rules and they can be used throughout the rule. In this rule, notice that ?y-binding is visible and used within the RHS action of the rule.

The RHS action of this rule uses insert! which is a function provided by Clara to insert a new fact into working memory. The ->ThingA is a constructor call to make a new fact of type ThingA that uses the value of the ?y-binding as some part of its initialization, which isn’t necessary to show here.

Now consider this rule:

(defrule rule-b

[FactType1 (constraint-fn x :some-value) (= ?y y)]

[?fact2 <- FactType2 (join-fn ?y z)]

=>

(insert! (->SomeFactType ?y ?fact2)))

This rule has two conditions. The second condition is responsible for joining a fact matching the first condition to a fact matching the second condition. Some function called join-fn is called to test values coming from different facts. The first argument to join-fn is ?y, which is a variable binding bound to the y field value of a fact matching the first FactType1 condition. The second argument to join-fn is z, which would be the z field value of a fact matching fact type FactType2. This condition demonstrates the ability to join more than one fact together in a rule by utilizing bound variable bindings across conditions.

Also, notice the second condition of this rule starts with ?fact2 <-. The <- is preceded by a variable binding symbol and followed by the rest of the condition. This means that ?fact2 is bound to the whole fact that matches the second condition, rather than just a field value of a fact as is the case for the ?y binding.

Both fact-level and field-level variable bindings can be used throughout a rule. The RHS action of this rule shows that it can refer to the fact-level binding ?fact2.

What problems do rules engines solve?

Rules engines are well suited in applications where there is a significant amount of conditional logic performed.

To make this more concrete, let’s look at an example.

Consider the following problem:

- Determine if the person may be hypertensive (high blood pressure).

- A person is considered hypertensive if a blood pressure:

- Has systolic value > 140 AND

- Has diastolic value > 90 AND

- Was taken in the last year

- Blood pressures come from separate systolic and diastolic result facts.

- A blood pressure reading is formed from a systolic and diastolic result taken on the same day.

Functional approach

When thinking of a “functional” approach to this, the general idea is to create simple, cohesive functions for each part. Then compose the functions together to solve the problem.

We may end up with something like the following:

(defn bp-for-type [bp-type results] …)

(defn combine-bps [systolic-bps diastolic-bps] …)

(defn bps-in-period [current-date period-type bps] …)

(defn bp>value [bp value] …)

(defn hypertensive? [current-date results]

(->> (bp-for-type :diastolic-bp results)

(combine-bps (bp-for-type :systolic-bp results))

(bps-in-period current-date :year)

(some #(bp>value % {:systolic 140

:diastolic 90}))))

Five functions were defined:

bp-for-typeis a filter ofresultsbased on their type, e.g.:systolic-bpvs:diastolic-bp.combine-bpscreates each possible pair of blood pressures fromsystolic-bpsanddiastolic-bpswhen both were taken on the same day.bps-in-periodis a filter of pairedbpsbased on if they occurred within the last period, e.g.:year, relative to thecurrent-date.bp>valuetests if a givenbphas a greater value than thevaluegiven.- The value is expressed as a map with

:systolicand:diastolickeys used for the constituents that make up a blood pressure value.

- The value is expressed as a map with

hypertensive?answers the question whether the person is hypertensive or not based on theresultsand thecurrent-date.- This function implements the specific logic to satisfy the initial problem statement.

This approach is reasonable for a case like this. Composing these functions together makes for a modular approach. These functions are general and have potential for reuse if new problems come along later that need to be solved with similar logical parts.

Problems do not typically stay the same over time. The problem often evolves to ask more complex questions or ask different, related questions. Let’s look at a few examples of evolving our initial problem statement.

Find hypotension

- Determine if a person is hypotensive (low blood pressure).

- A person is considered hypotensive if a blood pressure:

- Has systolic value < 90 AND

- Has diastolic value < 60 AND

- Was taken in the last year

In this scenario, we still want to look for hypertension, we just also want to look at hypotension as well. Continuing with the initial functions introduced for hypertension, we can solve this by adding the following:

(defn bp<value [bp value] …)

(defn hypotensive? [current-date results]

(->> (bps-for-type :diastolic-bp results)

(combine-bps (bps-for-type :systolic-bp

results))

(bps-in-period current-date :year)

(some #(bp<value % {:systolic 90

:diastolic 60}))))

bp<valuetests if the givenbphas a lesser value than thevaluegiven.hypotensive?is the same ashypertensive?, but it tests for a blood pressure with a value less than 90/60.

However, this may not be a satisfying solution the problem. What if it is undesirably expensive to recompute the finding of blood pressures that are used for both the hypertension and hypotension cases? Then the obvious solution is to extract out the common part into some intermediate state so that it can be reused to ask both questions.

(defn hypertensive? [bps] …)

(defn hypotensive? [bps] …)

(let [bps (->> (bps-for-type :diastolic-bp results)

(combine-bps (bps-for-type :systolic-bp

results))

(bps-in-period current-date :year))]

{:hypertensive? (hypertensive? bps)

:hypotensive? (hypotensive? bps)})

For the sake of example, the intermediate state is just bound as a local variable via Clojure’s let binding construct. Then we make a map that holds the answer to the two logical branches we are interested in. Notice now that the functions hypertensive? and hypotensive? have been changed to take bps, which are pre-paired and filtered blood pressures.

This solves the problem of reusing the intermediate computation, however, we had to reorganize our existing code to do it. If a new branch of logic is added later, this issue may come up again. We may have to keep pulling out intermediate results to be used for different logical branches. This can become a lot to manage and hard to maintain if the logic becomes complex.

Filter BPs from ER visits

Let’s consider another extension to the original problem of finding hypertension. Now, there is a need to ignore blood pressures that occurred during an emergency room (ER) visit. This makes sense since they may not be accurate due to the person being on medication or in critical condition.

The requirements are extended as:

- Cannot use blood pressure readings that occurred during an emergency room visit.

- Emergency room visits come from encounter facts.

The following extensions to the original hypertensive? solve this:

(defn visits-for-type [visit-type encounters] …)

(defn has-visit? [bp visit] …)

(defn hypertensive? [current-date results encounters]

(let [er-visits (visits-for-type :er-visit encounters)

has-er-visit? (fn [bp]

(some #(has-visit? bp %)

er-visits))]

(->> (bps-for-type :diastolic-bp results)

(combine-bps (bps-for-type :systolic-bp

results))

(remove has-er-visit?)

(bps-in-period current-date :year)

(some #(bp>value % {:systolic 140

:diastolic 90})))))

visits-for-typeis a filter ofencountersbased on their type, e.g.:er-visit.has-visit?determines if thebpoccurred during thevisit.hypotensive?now must take a new argument,encounterssince it now has to incorporate logic about ER visits.encountersare filtered by type:er-visit.- A local function

has-er-visit?is defined to determine if abphas any of the known:er-visitvisits. - After blood pressures are combined we

removeany that return a truthy value from thehas-er-visit?function.

Adding new complexity to the initial logic caused the function to have to be reorganized. We had to add the encounters argument to hypertensive? so that it could use this new input somewhere within the functions being chained together. Also, we had to decide where to incorporate the logic to remove blood pressures with ER visits. Also, it is important that function inputs are visible to the part of the composition “stack” where they are needed. The result is just a lot of manual “wiring” together of function inputs and outputs. This is all order sensitive as well. Similar to the hypotension problem shown previously, this can become hard to maintain.

As the complexity of the problem increases over time, this approach becomes increasingly brittle and difficult to reason about. This is what Rules engines are meant to help solve. The rules engine handles the details of ordering and wiring together the logic, as well as storing intermediate match results to avoid redundant computation.

Rule-driven approach

Let’s look at a rule-based approach to solving the same problem:

(defrule systolic-bp

[Result (= :systolic-bp type) (= ?val value)]

=>

(insert! (->SystolicBp ?val)))

(defrule diastolic-bp

[Result (= :diastolic-bp type) (= ?val value)]

=>

(insert! (->DiastolicBp ?val)))

(defrule combined-bps

[SystolicBp (= ?date date) (= ?sys-val value)]

[DiastolicBp (same-day? date ?date) (= ?dia-val value)]

=>

(insert! (->Bp ?sys-val ?dia-val ?date)))

(defrule bps-in-year

[CurrentDate (= ?date date)]

[?bp <- Bp (same-year? ?date date)]

=>

(insert! (map->CurrentYearBp ?bp)))

(defrule find-hypertensive

[?bp <- newest-date :from [CurrentYearBp (and (< 140 systolic-val)

(< 90 diastolic-val))]]

=>

(insert! (->Hypertensive ?bp)))

(defquery query-hypertensive

[?h <- Hypertensive])

Five rules and one query are defined:

- The rules

systolic-bpanddiastolic-bpmatch eachResultthat has type:systolic-bpand:diastolic-bp, respectively. A fact type is defined for each case,SystolicBpandDiastolicBp. - The rule

combined-bpsmatches eachSystolicBpandDiastolicBppair when they occur on thesame-day?. Each pair has a fact inserted of typeBpto represent it in working memory. - The rule

bps-in-yeartakes theCurrentDateas a fact (presumably derived or given from somewhere else in the application or rules) and inserts aCurrentYearBpfor each of theBps found to be within thesame-year?as the current date. - The rule

find-hypertensivefinds anyCurrentYearBpthat has a value greater than 140/90. If it is found, aHypertensivefact is inserted into working memory.- The

Hypertensivefact holds a reference to the blood pressure that was found with a value greater than 140/90, which could be useful later to explain the result. - This rule uses an accumulator condition with the accumulator

newest-date, which just returns the newest fact matching this rule condition.

- The

- The query

query-hypertensiveallows for an external application to access theHypertensionfacts that were inserted, if any.

defquery defines a query and has the same syntax as defrule. The only difference is there is no RHS action. Queries allow for an external application to perform ad hoc queries into the state of working memory after rules have been fired. This is the typical way that an external application can interact and retrieve the results from running rules.

Now let’s look at how to extend these rules for our two different evolutions to the problem we discussed previously.

Find hypotension

To find hypotension along with hypertension, just add the following:

(defrule find-hypotensive

[?bp <- newest-date :from

[CurrentYearBp (and (< systolic-val 90)

(< diastolic-val 60))]]

=>

(insert! (->Hypotensive ?bp)))

(defquery query-hypotensive

[?h <- Hypotensive])

find-hypotensiveis the same asfind-hypertensivefrom before, but looks forCurrentYearBpfacts with a value less than 90/60. The rule inserts aHypotensivefact when it is fired.query-hypotensiveallows the consumer to findHypotensivefacts in working memory after rules have fired.

Adding a new branch of logic did not require any changes to the existing rules. Also, this new rule was able to use all of the same facts as the hypertension-based rules.

Filter BPs from ER visits

To ignore blood pressures that occur on an emergency room visit, the following changes could be made to the rules:

(defrule er-visit

[Encounter (= :er-visit type) (= ?date date)]

=>

(insert! (->ErVisit ?date)))

(defrule combined-bps

[SystolicBp (= ?date date) (= ?sys-val value)]

[DiastolicBp (same-day? date ?date) (= ?dia-val value)]

[:not [ErVisit (same-day? date ?date)]]

=>

(insert! (->Bp ?sys-val ?dia-val ?date)))

- The rules

er-visitmatch eachEncounterthat has type:er-visit. It inserts anErVisitfact when fired. - The rule

combined-bpsthat was previously defined is updated here to use a negation condition to skip any blood pressure pairs that occur on the same day as anErVisit.

The logic for finding ER visits can be done separately from the rest of the existing rules. The rules allow us to decouple the unrelated parts of the logic and combine them in a way where we do not have to be concerned with how they are ordered or wired together.

How rules engines work

Now it is time to look at how rules engines work in a little more detail. Having this understanding can make you more informed on the performance characteristics and general flow of execution within the rules engine.

As mentioned earlier, nearly all modern forward-chaining rules engines are based on some variation of the Rete algorithm. The algorithm was introduced by Dr. Charles Forgy’s1982 paper, “Rete: A Fast Algorithm for the Many Pattern/Many Object Pattern Match Problem”. The Rete algorithm organizes rule conditions into graph that we will call the Rete network.

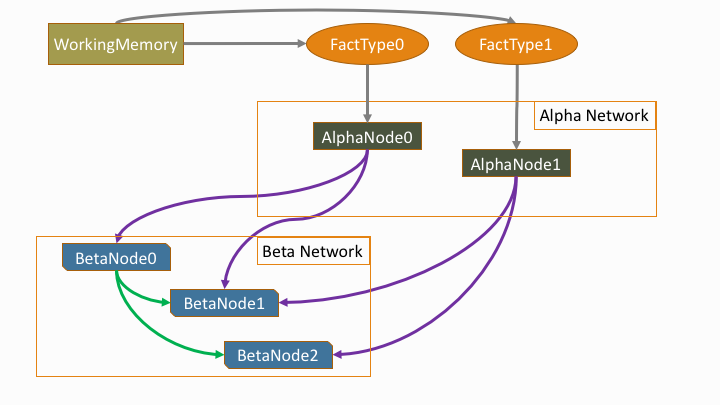

The typical layout of a rete network is something like:

The facts of the working memory distribute through the nodes of the network by following the directed edges. The fact types of rule conditions are checked first. When facts match the fact type checks, they are propagated to the children nodes.

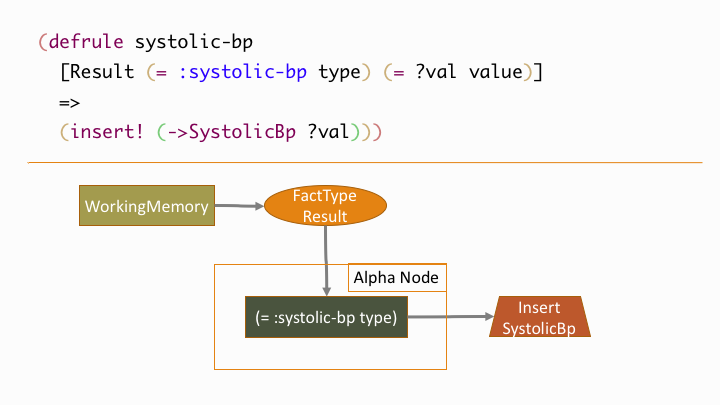

Alpha nodes

The first layer of nodes facts are propagated through are the alpha nodes. Alpha nodes are sometimes called one-input nodes. This is because alpha nodes are responsible for testing constraints in rule conditions that only involve one fact at a time. Using the rule systolic-bp from the hypertensive problem as an example, we can see how it is translated to a Rete network.

The alpha node here is shown to be testing the constraint (= :systolic-bp type) which can be done given only a single Result fact at a time. When the constraint is satisfied, this alpha node propagates the results to its children nodes. Here it only has a single child node. The red trapezoid node is called a ProductionNode and it represents a fully satisfied, activated rule. The node is labeled here with the rule’s RHS action to make it clear what it represents.

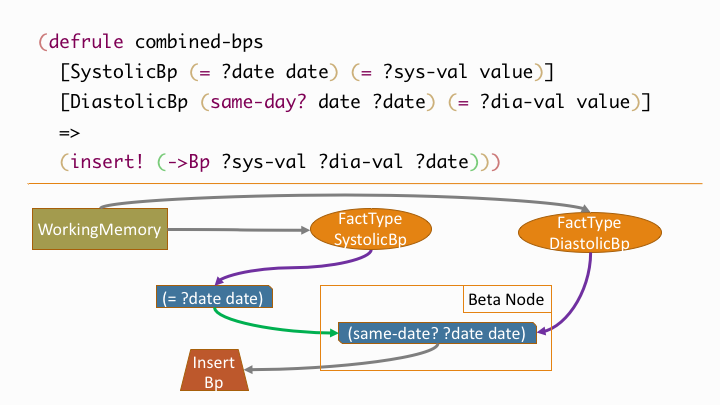

Beta nodes

The children of the alpha nodes are the beta nodes. Beta nodes are sometimes called two-input nodes. This is because beta nodes typically have two incoming edges in the Rete network. Beta nodes are responsible for joining together two or more facts based on some constraints. Using the rule combined-bps from the hypertensive problem as an example, we can see how it is translated to a Rete network.

The beta node highlighted here is the node responsible for joining a SystolicBp fact to a DiastolicBp fact when they satisfy the constraint (same-day? date ?date) based on their associated ``date` field values.

Beta nodes have memory that stores the input that comes from each incoming edge. In this way, if the beta node receives input from one side at some point in time and doesn’t have a match, it remembers it. Later, if input comes from the other side that does match, it will be able to make the new match. This is one way the rules engine avoids recomputing intermediate results. When working memory changes, only the path through the network affected by that change must perform work.

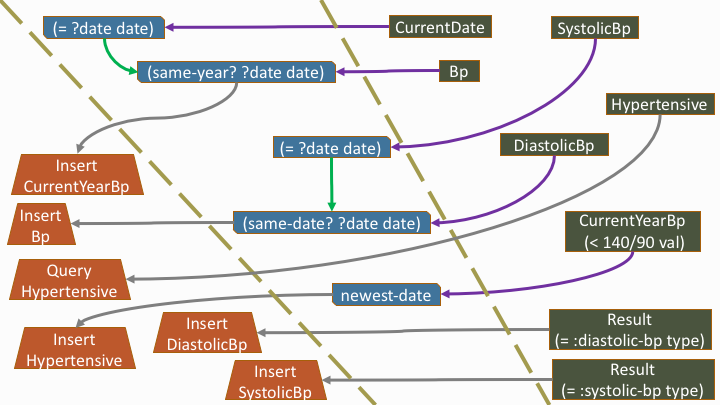

Full Rete network

Putting together all of the rules from the original hypertension example, the Rete network may look like:

More on Clara rules

If the reader is interested in more details on Clara rules, see the Clara rules docs. Along with this, Ryan Brush, the creator of Clara rules, has given a couple great talks on Clara’s features that even include live demos. These are available on YouTube: